Class Act: Designing for Collaborative Learning Environments

If you attended college before 2000, you got your coffee at the 7-11, raced to class held in a lecture hall with stadium seating and fluorescent lighting, crossed the college green to the library, then hunkered down in an isolated study carrel to work. Today, learning, lounging, and lattes are all in one daylight-filled building.

Lighten Up

The lecture hall is still a fixture, but on campuses throughout the US, traditional learning environments now include spaces adapted for team-based learning and collaboration. The formal vestibule is now typically a light-filled atrium with a Starbucks, Wi-Fi puts the library in every backpack, and comfortable seating in various configurations provides space for project meetings, tutorial sessions, individual research or just lunch. Upstairs, classrooms are designed for active learning. Movable desks, surrounding whiteboards, and technology-rich environments have replaced spaces designed for last century’s chalk & talk.

Comfort and Collegiality

If you have a good idea, share it. Colleges are finding that informal lounge space within an academic building results in a high level of spontaneous creativity and opportunities for trying out new ideas. As described in Planning for Higher Education [i], spaces that give students greater visibility into what is going on nearby, provide a place to take breaks between classes without leaving the building. They also lend themselves to unexpected encounters with peers and faculty, which lead to better studying experiences.

The George Washington University Science and Engineering Hall (SEH) provides opportunities for impromptu collaboration and learning throughout the building in addition to classrooms and labs.

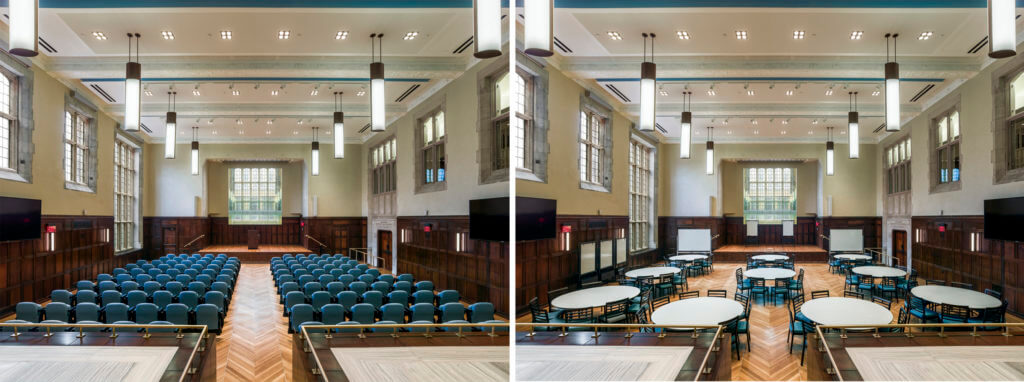

“There is a more social aspect in classroom buildings than there used to be,” says Helen Diemer, FIALD, MIES, LEED AP, Principal of The Lighting Practice, “and a crossover among building types that used to be programmatically isolated. Now colleges are asking for a place where students can work, study and socialize, and that may also be quickly adapted for events. It’s not always new construction. With a sensitive renovation, historic facilities can feel warm and contemporary.”

New Rules

Creating a mix of private and public spaces allows for collaboration and privacy. If lounge areas contain supporting materials such as whiteboards, students can turn social spaces into study spaces. Using furniture and lighting that can be adjusted or changed by students maximizes their comfort and desire to use the space. According to Campus Technology [2], if students and educators are able to move the furniture, they will reposition it to suit their needs, creating a more engaged environment for the task at hand.

“It’s definitely a challenge to illuminate spaces with various functions,” says Emad Hasan, Assoc. IALD, LEED AP BD+C, Associate at The Lighting Practice. “Flexible environments require a flexible lighting system, and it has to be easily controlled to address different functions. In designing a space like that, we try to provide various layers. When you enter a space, the lighting can start off with a feeling that you are in a public area and welcome to lounge and relax, or can be adjusted to allow for a meeting type of environment.”

Active Learning

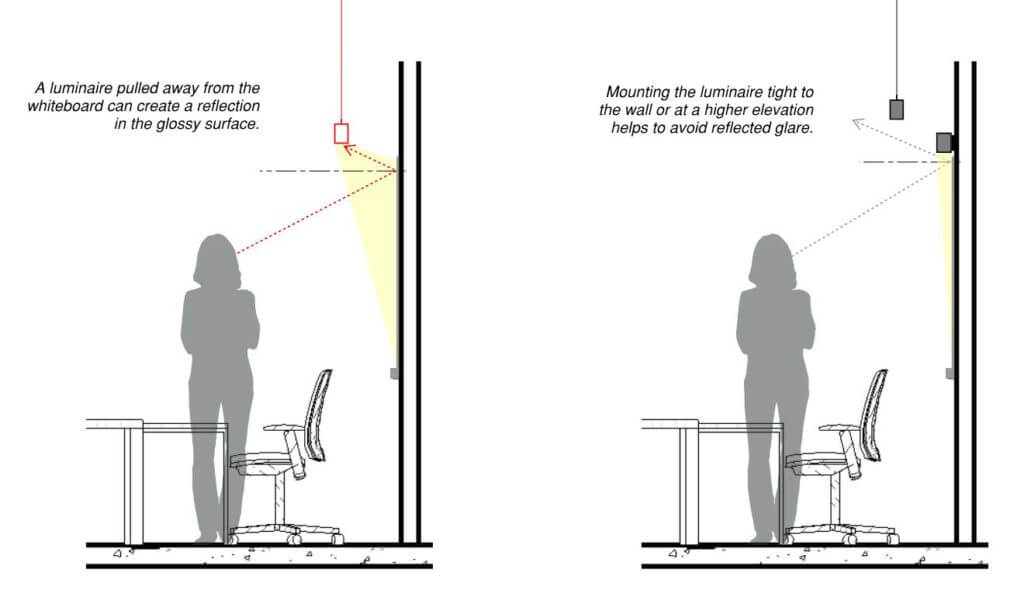

A life-sciences building currently under construction at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County has been designed with all active learning classrooms. Tables are round, a wireless microphone allows the professor freedom of movement, video monitors and whiteboards are mounted on all four walls. With no designated front of the room, the lighting system must provide adequate light for however the furniture will be arranged. Special consideration must also be made when illuminating a room filled with highly reflective materials like whiteboards, digital screens, or glass partitions.

Created by The Lighting Practice

“At UMBC, we illuminated the perimeter whiteboards directly by using linear fixtures along their top edge,” explains Matt Fracassini, MIES, LEED AP BD+C, Project Manager at The Lighting Practice. “Since the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, an image of the light source would have been visible in these reflective materials if the fixtures were pulled too far away. We addressed these and other task-specific concerns while creating ambient lighting that is so comfortable and unobtrusive, no one notices it.”

While competition to attract students and researchers may be driving new construction and renovation projects on college campuses across the country, the result is an environment that will help many different kinds of learners to step into the light.

[1] Doshi, A., S. Kumar, and S. Whitmer. 2014. Does Space Matter? Assessing the Undergraduate “Lived Experience” to Enhance Learning. Planning for Higher Education 43 (1): 1–20

[2] Villano, M. 2010. 7 Tips for Building Collaborative Learning Spaces. Campus Technology, June

Project Spotlight: University of Pennsylvania Hill College House

Philadelphia, PA, USA

The University of Pennsylvania’s Hill College House is a 1960 dormitory designed by Eero Saarinen to emulate a small, self-sufficient village. This six-story masonry building is home to nearly 520 students. The building’s interior layout fosters a sense of community and social interaction through shared amenity spaces centrally located like a town square. During the day, the building is filled with vibrant light from the clerestory level above.

The restoration team, collaboratively led by Mills + Schnoering Architects and Floss Barber, walked a fine line: honoring the original design intent while updating the building’s systems and aesthetics to meet current-day demands. The Lighting Practice set out to update the existing interior lighting system to meet university standards and required light levels for student residences and corridors. While the directive was straightforward, the execution was anything but.

Lighting Challenge

Eero Saarinen constructed Hill College House from concrete slabs, limiting TLP’s ability to incorporate recessed lighting. With only two inches between the foundation and drop ceilings, the team had to be selective when locating fixtures. TLP coordinated the placement of recessed downlights within existing waffle slabs in the concrete, which also had to align with the new 4×4 ceiling grid. Flush ceiling-mounted fixtures and decorative pendants were used where depth was limited. Maintaining the desired aesthetic, required light levels, and wayfinding were also factors when determining fixture placement.

Hill College House’s impressive atrium was originally lit by metal halide fixtures attached to a truss system controlled by pulleys. The trust needed to be manually lowered when maintenance was required. The Lighting Practice developed a 20th-century solution. TLP replaced the metal halide fixtures with LED and specified a mechanical truss, so the system can be maintained with a push of a button.

The building’s exterior and surrounding landscape were previously lit solely for safety. Floodlights were used to illuminate the pedestrian walkways and surrounding “moat,” creating a fortress-like appearance rather than that of an inviting destination. TLP removed the floodlights and incorporated bollards along the “moat” to illuminate the walkways and landscape at the pedestrian level. By focusing light at the building’s entrance and along the pedestrian bridge, a welcoming effect draws in residents and visitors.

Hill College House is once again a vibrant community that engages and supports the students who live there. The building was designed to LEED Silver certification standards.

Credits

Owner: University of Pennsylvania

Architect: Mills + Schnoering Architects, LLC; Interior Design: Floss Barber; Landscape Architect: OLIN; Materials Conservation: Keystone Preservation Group; Construction Management: INTECH Construction, Inc.; Estimating: Becker & Frondorf; Envelope Consulting: Edwards & Company; Structural Engineer: Keast & Hood; Civil Engineer: Pennoni; MEP/FP Engineer: AHA; Lighting Design: The Lighting Practice; A/V and Acoustic Design: Metropolitan Acoustics

Photography respectively by Aislinn Weidele